President Donald Trump announced on June 19 that he will decide in the next two weeks whether the United States will join Israel’s military campaign in Iran. If he decides in the affirmative, the United States will be entering a war in the Middle East with ambiguous objectives (including but not necessarily limited to countering nuclear proliferation), an incomplete strategy, and a high risk of entrapment.

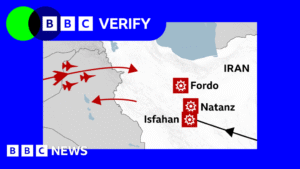

This prospect has, understandably and rightly, evoked painful memories of the Iraq war for many Americans. As a president who claimed to oppose the Iraq war, Trump, along with his allies, has tried to frame possible U.S. military intervention in Iran in limited terms, with a focus on the single target of the underground Fordow nuclear enrichment facility, which Israel may not be capable of destroying on its own. This may be an accurate reflection of Trump’s intentions, but even that decision would carry major risks, including Iranian retaliation against U.S. military facilities in the Gulf or terrorist attacks against Americans abroad, which could prolong and deepen U.S. involvement in Iran. Even if a limited U.S. operation goes according to plan with no retaliation, a decision to intervene in the conflict would, rather than end Iran’s nuclear program, make a sustainable solution harder to achieve.

POLICY PATHOLOGIES

U.S. and Israeli statements on the war in Iran display two of the most prominent pathologies of American foreign policy over the last century. The first is a belief that airpower can be employed to achieve strategic, not just tactical, objectives. As Israel presents it, the Israel Defense Forces and the Mossad are in the process of destroying Iran’s nuclear enrichment capacity and other critical sectors of its nuclear program. Fordow, which only the U.S. military can destroy from the air with 30,000-pound bunker busters, is portrayed as the final redoubt of the Iranian enrichment program: take out Fordow and its advanced centrifuges, and Iran’s nuclear program will be effectively neutered, eliminating a dangerous threat to international security.

Although U.S. officials express confidence that the GBU-57 bomb can break through the 260 to 360 feet of concrete protecting Fordow, this is an untested proposition. According to the U.S. military, the facility is so deeply buried that it will likely require dropping multiple GBU-57 bombs with exacting precision to breach the underground complex. It would be a mistake to bet against the U.S. Air Force, but it would be unwise to discount the possibility that the mission could fail—a contingency the Trump administration would have to be prepared for.

An unsuccessful attempt on Fordow would not just position Iran to reconstitute its nuclear program quickly. It would also raise the incentive for Iran to develop a nuclear weapon to deter future attempts against its program. Meanwhile, the alternative to airstrikes would be an attack that would involve deploying U.S. ground forces to attack Fordow, putting U.S. service members at greater physical risk and raising the probability Iran would retaliate directly against U.S. installations in the Middle East.

A U.S. decision to intervene would make a sustainable solution harder to achieve.

The second pathology is a misplaced confidence in the ease with which an adversarial regime can be toppled and an almost blind faith that a successor government will prove better than its predecessor. Israel has become increasingly forthright that its objective in Iran is to bring about the fall of the Islamic Republic. Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, who has long advocated for regime change, said Israel is creating “the means to liberate the Persian people” and claimed that killing Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei would “end the war.” Trump himself has occasionally hinted at broader ambition, claiming that the United States is not seeking to kill Khamenei but adding the ominous caveat “at least not for now.”

Although the leadership of the Islamic Republic is deeply unpopular among large swaths of the Iranian population, regime change would be far from an easy feat. Contrary to Netanyahu’s claims, the killing of the supreme leader is unlikely to precipitate the collapse of the Islamic Republic by itself. After 46 years, the institutions of the state are well entrenched, and the absence of an obvious successor to Khamenei does not mean one cannot be found. Advocates of a strike on Khamenei sometimes point to Israel’s decapitation of Hezbollah’s leadership last year. Yet even Hezbollah continues to function in Lebanon, and Iran is far more powerful.

Accordingly, toppling the Iranian regime militarily would likely require a large ground force. The Israel Defense Forces lack the expeditionary capability and the scale to play that role, which would mean U.S. forces would have to take it on. The American public rightly has no appetite for another Middle East misadventure; recent polling indicates that a majority of Americans oppose all military intervention in Iran.

ILLUSORY SUCCESS

Even in the event that the United States and Israel “succeeded” in their goals of destroying Fordow or even ousting the Islamic Republic, these would likely be ephemeral accomplishments or Pyrrhic victories. Destroyed equipment can be rebuilt. A tyrannical government can be replaced by an even more rapacious one. And even the most well-intentioned actions can produce the opposite of the intended result. Of the many lessons U.S. policymakers should have learned over the last 25 years, one of the most important is that military success translates imperfectly, if at all, into political success.

Destruction of the Fordow facility would inflict a serious blow to Iran’s nuclear ambitions by setting back its enrichment program. But even a successful operation would not deliver a coup de grâce to Iran’s nuclear activities, certainly not in the middle to long term. Some reporting has suggested that the Iranians may have expanded Fordow, allowing for the storage of nuclear technology in unidentified locations in the complex that could survive a U.S. or Israeli military mission untouched. If this is the case, an attack on Fordow would buy less time than anticipated.

Even in a best-case scenario in which all centrifuges and other nuclear-related equipment and infrastructure are destroyed, Iranian scientists would retain the knowledge to rebuild. Given that most of Iran’s highly enriched uranium stockpile is expected to survive a war (since it is believed to be widely dispersed across the country and much harder to destroy than delicate centrifuges), Iran would not be starting its program from scratch. And Iranian leaders would have a strong incentive to take every precaution to avoid detection this time, a threat that would be exacerbated if Iran withdraws from the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty, which authorizes oversight of nuclear facilities by the International Atomic Energy Agency. In that case, if Israel or the United States were to discover ongoing Iranian activity, the only alternative to a negotiated solution would be more strikes. Although Trump has proved willing to suspend military operations that risked mission creep, such as recent strikes on the Houthis in Yemen, future presidents might find it more difficult. Far from Fordow being a one-off affair, it could presage continued warfare, a more costly form of Israel’s strategy of “mowing the grass” in Lebanon and Gaza.

The American public rightly has no appetite for another Middle East misadventure.

Nor would regime change be a reliable solution to Iran’s nuclear ambitions. If the Islamic Republic collapsed, it is as likely that the regime would be replaced by a government hostile to U.S. and Israeli interests as by one that is more aligned with them. During leadership vacuums, the most organized elements in a society often triumph. After decades of repression against the opposition and civil society, the Iranian military or security services are likely to emerge as the dominant actors.

Even a more pro-Western or democratic government would not necessarily adopt a fundamentally different posture on Iran’s declared right to nuclear enrichment; such a government might feel the same imperative as the current regime to develop a nuclear weapon. Another possibility is that Iran could descend into chaos, with competing factions located in different parts of the country. The presence of radioactive material in such an environment would be alarming, and chronic instability in a country Iran’s size that sits astride important trade routes would pose any number of security challenges.

Previous U.S. and Israeli occupations do not instill confidence that either country could facilitate a transition to a new regime that is both friendly and enduring. The U.S. occupation of Iraq is literally a case study in foreign policy catastrophes, while American interventions in Afghanistan, Libya, and Somalia were also failures. For Israel’s part, over 50 years of occupation in the West Bank and Gaza have produced extraordinary tragedy for both Palestinians and Israelis. Israel’s installation of a pro-Israeli Lebanese president in the 1980s led to his assassination amid a brutal civil war that devastated Lebanese society. Twenty years of occupation of Southern Lebanon led to high Israeli and Lebanese casualties and created the conditions that abetted Hezbollah’s rise to power. There is no reason to think regime change in Iran would be any different than in past U.S. and Israeli experiences.

NOT ENOUGH TIME

Advocates of U.S. and Israeli military intervention argue that, even if it will not end Iran’s nuclear program, it buys time, extending Iran’s timeline for achieving breakout and building a weapon. (Israeli military sources say that attacks so far have delayed Iran a few months.) Time is of course valuable, but when it elapses, the United States and Israel will again confront a decision between negotiating and undertaking further military action. The relevant objective is not delay, but preventing Iran from going nuclear—and it is from this perspective that Israeli and potential U.S. military action should be evaluated.

If Israel and the United States refrain from pursuing regime change in Iran, it is conceivable that the leaders of the Islamic Republic would conclude that the risks to the regime of escalating its nuclear program or rushing to breakout are too great to take on. But it is also possible that the regime will draw the exact opposite conclusion: the only way to protect the regime from external enemies is developing a nuclear deterrent. It is presumably not lost on Iranian leaders that governments that give up their nuclear program (Libya, Iraq) are toppled, while those that do not (North Korea) survive.

And even if such a gamble pays off, setting Iran’s nuclear program back without spurring a rush to a nuclear weapon, it is a particularly bad bet when compared with the alternative: an agreement that imposes robust verification on Iran’s nuclear activities and puts enough time on the clock to detect and preempt a breakout. Under these conditions, exhausting every possibility to achieve such an agreement is the only responsible course. A two-week delay should offer Trump and senior members of his administration time to register this reality and do what is required to strike a deal that would end the conflict. If not, Trump will be leaving U.S. and regional security dependent on the outcome of a reckless gamble that could draw the United States further into the Middle East and create another foreign policy debacle that haunts Americans for decades.